Google Glass: Epic fail or epic pretotype?

Google Glass is still widely considered one of the great failures of the tech world. Even years after being pulled from the market, it’s still the product that people love to hate - the epitome of a bunch of tech nerds squirrelling away making an ugly, useless product that no-one actually wants to wear.

But what if we flip this on its head, and see the commercial ‘failure’ of Google Glass as a stunning example of advanced pretotyping?

This is how Alberto Savoia - the founder of pretotyping and Google’s Innovation Agitator Emeritus - explains Glass: “The way I see it, Glass was never produced in mega quantities, quite the contrary. The attitude I sensed while I was at Google was, ‘It would be great if this catches on, but let's move slowly and collect data on adoption/usage. Not launch it like, say, Apple Watch with millions of units for sale.’”

Central to Google Glass’ 2013 launch was the Google Explorer program, where potential customers were invited to use the hashtag #IfIHadGlass on Twitter to qualify as a potential early adopter of the product. 8,000 people were selected and invited to pay $1,500 and visit the Google office to pick up their unit and receive training. This is how Exponentially’s founder Leslie snapped up his pair, which now sits in his ‘Mini Tech Museum.’

Leslie’s Google Glass (and yes, it’s a pretty accurate representation of Leslie’s face, in case you were wondering…. :P )

“At the time this was a risky bet which needed skin-in-the game from early adopters like me that were willing to invest real money as a way to experience the future. The risk is always that it can go to zero, but looking back, I’m pleased I could play a small part in this experiment. Only Google and the Glass team know what the hundreds of micro lessons were that they learned through this process, and how they were folded into future products like the watch, Android cards, on top of all the behavioural and timing insights”

This was essentially the most advanced pretotype the Google Glass team conducted before the product’s wider beta launch in 2014.

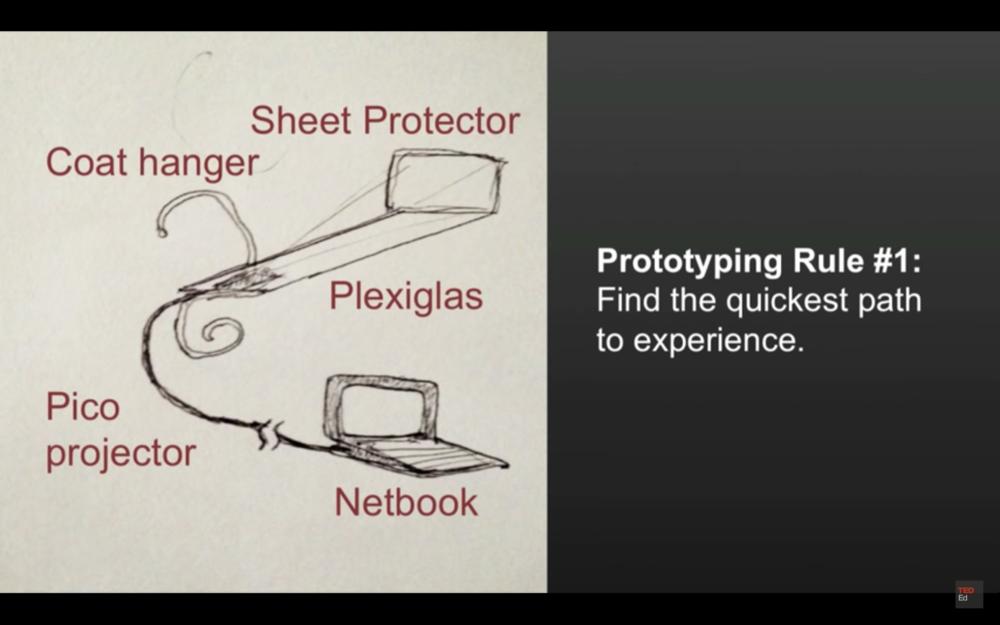

It was the pretotype with the most ‘skin in the game’ in a product development process that used a series of incredibly complex pretotypes. Initially, the Glass team started with a Pinocchio pretotype. First, they asked one of the core pretotyping questions: “How can we test this idea in 24 hours for $0?” Then, they used a coat hanger, sheet protector and Plexiglas hooked up to a netbook and projector to test the core idea of Google Glass. This was one of their early pretotypes:

One of the earliest Google Glass pretotypes. Source

As Tom Chi, member of the Google Glass team, explains in this TedEd talk, “Through the process of rapid prototyping you are able to learn very quickly.” The Pinocchio pretotyping method - what Chi calls ‘rapid prototyping’ - is interesting in validating ideas by building fast, low-cost mock-ups of products that allow you to test the core concepts and assumptions that sit at the heart of an idea. Think of it as innovation and product development meets MacGyver:

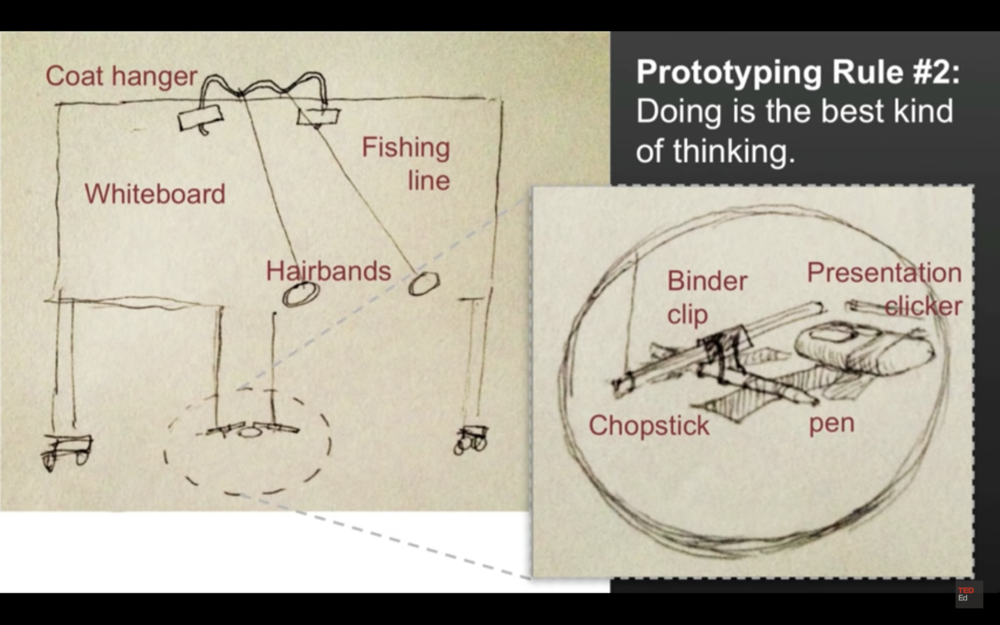

Rather than spending weeks or months developing complex (and expensive) prototypes, Chi and the Google Glass team used “materials that move at the speed of thought to maximise [their] rate of learning.” They developed another Pinnochio pretotype to test the gestures that people might use to control the glasses - using clay, hairbands, fishing line, a coat hanger, and a whiteboard:

One of the early pretotypes of Google Glass. Source

“Ultimately what it taught is we probably shouldn’t have this in the product. It taught us a lot of things about the social awkwardness of it and some of the ergonomic aspects of it that you couldn't have figured out just by thinking about it,” says Chi. “Doing is the best kind of thinking.”

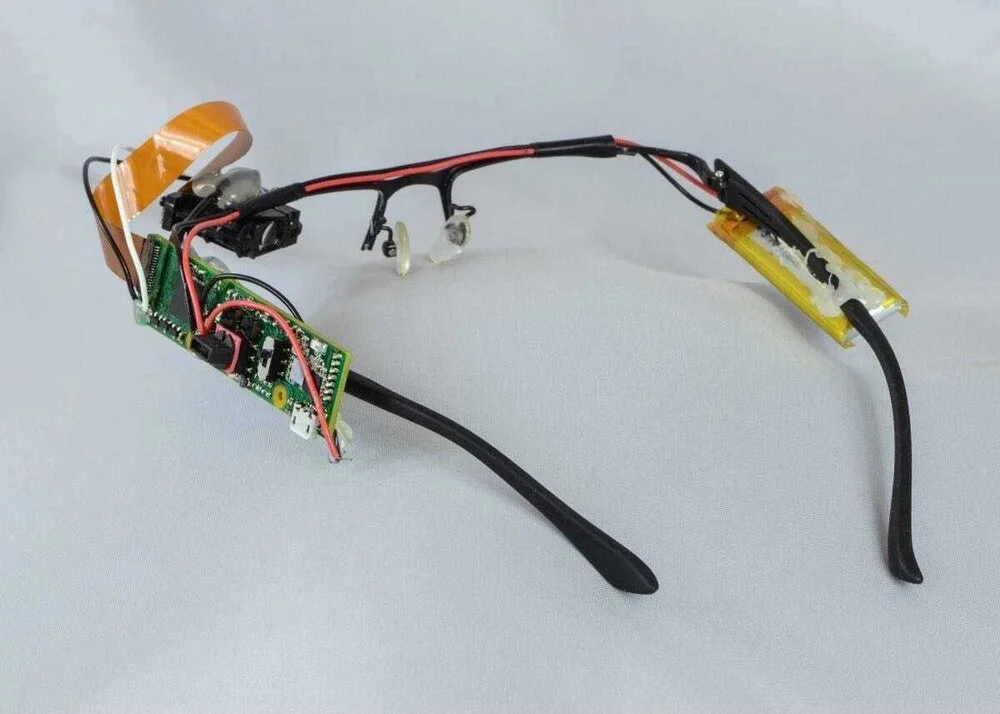

Ed Keyes was also on the Google Glass team; in our Pretotyping Slack channel, he talked us through one of the later prototypes (or, more advanced Pinnochio pretotype) that he created to test for specific things like wearability, notifications, and gestures:

Ed Keyes’ late-stage Pinnochio pretotype for Google Glass. For a walk-through the history of wearable devices, including Ed’s pretotype, check out this online exhibition.

“At the time, the other Glass prototypes were literally torn-down cellphones strapped to your head, which nobody could stand using. So I tried to make something that people could actually wear around the office all day… It was actually even lighter than the final Glass product ended up, and it was functional enough to give you real email notifications and the like, so people could see how much they liked or hated having that sort of feature… It even had some stuff that didn’t make it into the final product, like a gesture sensor. When you got a notification, all you had to do is wave your hand vaguely by your head in a dismissive gesture, and the notification would disappear. It was a cute interaction, very natural.”

As Google continued to harness the power of pretotyping in its product development, the Pinnochio pretotypes got more complex, each with more ‘skin in the game.’ As Alberto explained in the Slack channel, “The size of the bet (or cost of the pretotype) can (and should) take into account the available budget. Further, big companies can (and should) make some crazy bets they can afford. It's not only good for the world in general, it's fun. As long as you explicitly accept that the likelihood of success is going to be low.”

This is why Alberto considers the Google Glass to be not a failure, but an advanced pretotype. Sure, there was a lot of skin in the game (both from Google and from customers, who were asked to invest time and effort into the Explorer program, and money if they were selected as early adopters), but ultimately Glass gathered a lot of useful data which has been iterated in into the more successful Glass Enterprise, raised important questions about privacy and safety, and informed the development of similar smart wearables that have since gone to market.

“I don’t think of Glass as a failure,” says Exponentially’s founder Leslie. “I’ve always thought Glass had a timing problem. Imagine being told in 2021 not to video anyone in public! We’ve gone from getting assaulted in a bar for using Glass (remember Glassholes?) to everyone fighting for airtime to post video of them filming themselves on Instagram, and TikTok!

I also see Glass as the precursor to Android Cards, the Android Watch, the Apple Watch, AR, VR and touch interfaces. I believe lessons from the Glass project informed future user interface decisions over time. I fired my Google Glass up last week and it’s pretty impressive tech after nearly a decade! Now if only I could mirror my Apple Watch to my Glass… maybe one day.”

Want to be a part of some epic conversations with world-leading innovators? Sign up to sign up for our Experiementer’s Edge newsletter to be able to join our free slack channel and join in the fun.